In the early 1990s, Bulletin Board Systems lived and died by what their sysops were willing to share. Utilities, door programs, scripts, and small hacks were passed around not because they were perfect, but because they solved problems that other sysops were almost guaranteed to have.

Aminet was one of the main arteries for that sharing in the Amiga world. If you built something useful, you uploaded it. Others downloaded it, adapted it, improved it, or simply used it as-is. That was the culture.

Deliverance was one of those tools.

It ran on my Amiga-based LightSpeed BBS and did exactly what it was designed to do. Callers used it. It worked reliably. And yet, it was never uploaded to Aminet for other sysops to use.

This isn’t a story about lost code.

It’s a story about confidence; or rather, the lack of it.

The problem Deliverance was written to solve

Aminet CDs were incredible resources. They contained vast collections of software, utilities, and experiments, but they were also physical media. A CD-ROM drive could only be in one state at a time, and a sysop could only be present so many hours a day.

Callers, however, didn’t operate on that schedule.

They logged in when they could, often late at night, between work shifts, whenever the phone line was free. Often, the software they wanted existed; it just wasn’t immediately accessible.

Rather than treat that as a user problem, Deliverance treated it as a workflow problem.

What Deliverance actually did

Deliverance was split into two broad areas of responsibility.

The online services, written by me in AREXX, handled user interaction: providing file/search access, taking requests, determining whether the relevant Aminet CD was currently mounted, and coordinating what happened next.

The offline services, written by a good friend of mine, Scott Campbell, monitored the system for CD changes. When the correct disc was inserted, those services would locate the requested file and complete delivery by emailing the file so it would be waiting the next time the caller logged in.

If the CD was online, the file could be delivered immediately.

If it wasn’t, the request wasn’t rejected: it was remembered.

The system respected intent. It finished the job even if conditions changed.

It wasn’t flashy. It didn’t try to hide the reality of spinning discs, limited drives, or human availability. It simply worked with those constraints rather than pushing them back onto users.

By the time it was in daily use, Deliverance was stable, predictable, and complete. It wasn’t a beta or an experiment, but a finished solution doing exactly what it was designed to do.

Why it was never uploaded to Aminet

Deliverance wasn’t kept private because it wasn’t useful. It was kept private because I wasn’t confident enough to show my code.

Specifically, my AREXX code (the part that handled the online services) felt exposed. It worked, but I was convinced it wasn’t “good enough” to be scrutinised by other sysops and developers. I assumed it would be pulled apart, its rough edges highlighted, and judged against standards I felt I hadn’t yet earned.

That fear outweighed the fact that the system was already in use and already helping people.

At the time, I didn’t frame it as insecurity. I framed it as caution. In hindsight, it was simply just a lack of confidence.

The binary executable rabbit hole

One memory that still stands out is the amount of time I spent trying to work out how to turn deliverance.rexx into a binary executable.

AREXX is a scripting language, executed by an interpreter. I knew that. And yet I spent hours chasing the idea that if I could somehow “compile” it (make it look like a proper binary) it would feel more legitimate, and perhaps safer to release.

What I was really trying to do was hide the seams.

I wanted the work to look finished, authoritative, untouchable. I wanted protection from judgement, even if I couldn’t have named it that way at the time.

In the end, nothing came of it. The script remained a script, and Deliverance remained unshared.

Do I regret it?

Yes. Now I do.

Not because I missed out on recognition or credit, but because Deliverance could have helped other sysops solve the same problem. And because the decision not to share it was driven by fear rather than quality.

The code worked.

The system worked.

People benefited from it.

That should have been enough.

Why write about this almost 30 years later?

With hindsight, what stands out isn’t the technology but the mindset behind it. Deliverance existed because I wasn’t comfortable treating partial availability as “good enough”. With more software than physical drives, the easy solution would have been to accept the limitation and move on. Instead, the system was designed to absorb that constraint so users didn’t have to.

That instinct (to finish the job rather than fence it) feels less common now, in a world where solving part of a problem is often considered sufficient.

Looking back, Deliverance represents an early example of something I still see today: capable people withholding useful work because they don’t feel “ready” to be seen. Because they assume their work must first be flawless, carefully presented, or protected from scrutiny before it’s worthy of sharing.

It doesn’t.

Deliverance wasn’t perfect. It didn’t need to be. It just needed to exist outside the machine it lived on.

This post isn’t an attempt to resurrect old software or rewrite history. It’s simply an acknowledgment of what fear of scrutiny can quietly cost, even when the work itself is sound.

Sometimes, when something genuinely works and genuinely helps, it’s worth sharing anyway.

References & Links

Aminet (Amiga software archive) https://www.aminet.net

ARexx (Amiga scripting language) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/ARexx

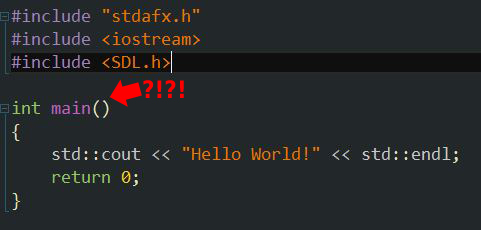

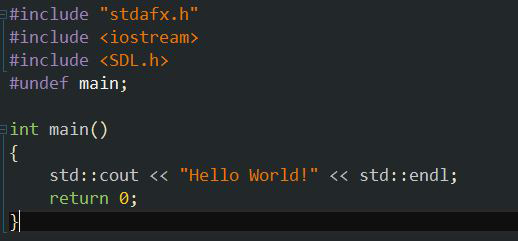

Look what happens when I attempt to include the SDL header. My main function becomes a member function and therefore won’t build.

Look what happens when I attempt to include the SDL header. My main function becomes a member function and therefore won’t build.